Auction Catalogue

‘He’s gone. We do not understand.

We only know as he turned to go

and waved his hand

In his young eyes a sudden glory shone

and we were dazzled by a sun-set glow

and he was gone.’

A poem inscribed in Sergeant Stephen Burns’s flying log book by his distraught mother, following his death in action in December 1943.

A deeply poignant ‘Dambuster’s’ uniform and extensive archive appertaining to Sergeant S. “Ginger” Burns, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, who flew as Rear Gunner in Pilot Officer Geoffrey Rice’s crew on the night of 16-17 May 1943: detailed to attack the Sorpe Dam, their ‘bouncing bomb’ was torn from its mountings when their Lancaster - flat out on the deck - hit the water at Vlieland: as his gun turret flooded up to his waist in salt water Burns was heard to exclaim, “Christ! It’s wet at the back, skipper”

Already a veteran of assorted operations in No. 57 Squadron, he was killed in action in No. 617 Squadron’s attack on the armaments factory at Liege in December 1943: on his last leave he had told his mother that he didn’t expect to live and to prepare his younger brother and sister for his imminent death.

The uniform and artefacts:

(i) The recipient’s R.A.F. tunic, trousers and side cap, as kept at his mother’s house for when he went home on leave; when he was reported missing his mother was so distressed that a Doctor had to be called, and she was put to bed with this uniform to comfort her.

(ii) His leather flying gloves, as worn on the Dams raid, together with a leather flying helmet and flying goggles, as given to his younger brother, Freddie, the former with ink inscriptions, ‘Thomas 145’ and S.G.F. 4’; and two embroidered A./G. brevets.

(iii) His brown leather wallet, as purchased during 617‘s stop over at Ras-el-Ma in French Morocco in July 1943, and as listed on the back of his R.A.F. Will.

(iv) A clock removed by the recipient from Lancaster ED-936 on its return from the ‘Dambuster’ raid; when his navigator, Richard MacFarlane, saw him removing the souvenir, he told him not to worry about it but Burns replied, “Waste not want not.”

(v) A wooden painted model of a Lancaster made for Burns by Richard MacFarlane and brought home by him on leave; an accompanying newspaper cutting refers.

The archive:

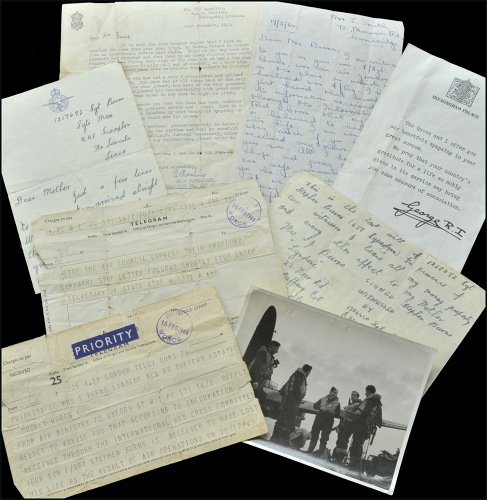

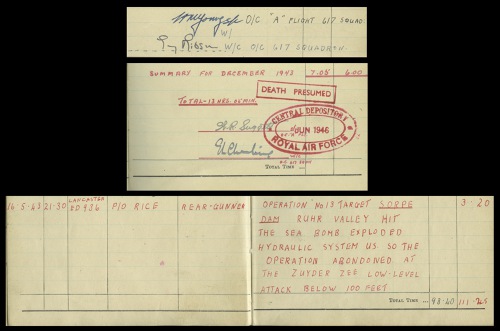

(i) The recipient’s R.A.F. Air Observer’s and Air Gunner’s Flying Log Book, with entries covering the period September 1942 up until his death in action on the night of 20-21 December 1943, the following page inscribed with the above quoted poem written by his distraught mother; the monthly entries signed-off by some notable senior officers, among them Guy Gibson, Cheshire, Maltby and Shannon, complete with red ink ‘Death Presumed’ and ‘Central Depository, Royal Air Force’ stamps, dated ‘Jun. 1946’.

(ii)

His hand written Will, undated, witnessed by Sergeants Thomas Maynard and Chester Gowrie, who would be killed with him in December 1943.

(iii)

His R.A.F. omnibus warrant, dated 10 August 1943.

(iv)

His Buckingham Palace condolence slip addressed to ‘Mrs. S. Burns’.

(v) Air Ministry telegram confirming the recipient’s death, dated 16 February 1944, following news received from the International Red Cross.

(vi) An impressive - and poignant - array of wartime period letters (22), several of them in the recipient’s own hand to his mother, among them his description of the King’s visit to Scampton and Gibson’s award of the V.C. and four letters sent from R.A.F. Coningsby after 617’s move there a few weeks before his death in action; also including Leonard Cheshire to the recipient’s mother, dated 21 December 1943, reporting that her son had failed to return from an operational sortie the night before, together with another to her husband, dated 10 February 1944, stating that he had no further news and that his earlier letter to his wife was not a ‘stock letter’ and that he meant everything he said; Group Captain Evans to the recipient’s mother, also reporting her son as missing on operations, dated 24 December 1943; letters from Mrs. E. Smith, the wife of Sergeant Edward Smith, who was killed with the recipient in December 1943, in the first of which she states that she still has hopes for their survival, only to have to write at a later date to confirm that the International Red Cross had now confirmed otherwise; communication from the Ministry of Pensions, dated 6 July 1944, informing the recipient’s mother that she was not entitled to any form of pension, and a communication from the Assessors of Income Tax, dated 6 December 1943, stating the recipient’s liability for tax was ‘NIL’; R.A.F. Casualty Branch message reporting that the International Red Cross had written with confirmation of the recipient’s death, dated 21 February 1944, and Air Ministry follow-up, dated in April 1944, with confirmation of his burial in the Parish Cemetery at Gosselies; an embroidered religious talisman, with reverse inscription from the recipient’s aunt, ‘’Hoping God will Guide you’; letters to the recipient from a girlfriend and his ‘best pal, Jim’, and a poem sent to him by ‘Vera’.

(vii) A fine selection of wartime photographs, including three studio portrait photographs of the recipient, in uniform, and another of him in flying kit, one of the former believed to have been taken on the day before he was killed in action; two group photographs including the recipient, taken during his training days; the recipient in uniform, with his brother John, in Naval uniform, and their mother, and another with his father, also in uniform; together with a quantity of 617 Squadron scenes, among them a Lancaster landing, marked on reverse, ‘Sgt Burns’, a Lancaster at night, Burns and two members of crew standing in front of their Lancaster at Ras-el-Ma in French Morocco, and another of the entire crew; a photograph of 11 ‘Dambuster’ pilots on R.A.F. Scampton’s mess steps the morning after raid, 617 Squadron aircrew outside Buckingham Palace, and Guy Gibson, H.M. the King and Air Vice-Marshal Cochrane inspecting a diorama of the Eder Dam; the recipient’s original grave in Belgium, marked by a white cross.

(viii) A birthday card from the recipient’s mother, annotated to say that he saw it although he was killed a week before his 23rd; together with three wartime period Christmas cards, all to the recipient from family and friends.

(ix) Assorted wartime newspaper cuttings, including “Dudley Airman in Dam Raid”, “Dam Raid Hero Dead” and “Dudley Family’s Part in War.”

(x) A quantity of post-war documentation, including a copy of Paul Brickhill’s The Dambusters, as sent to the recipient by 617’s ex-Intelligence Officer, with commentary on inaccuracies in the book; a menu for the occasion of the dedication of 617’s Memorial on 17 May 1987, signed by Richard Todd, a menu and Order of Service card for the raid’s 50th Anniversary, 19 May 1993 and assorted invitations for 617 reunions and related parking tickets.

(xi) A letter from Mrs. Janet Maynard, the mother of Flight Sergeant Thomas Maynard, who was killed with the recipient in December 1943, dated 8 October 1950, in which she reports on her visit to their graves in Belgium and encloses photographs.

(xii) A letter from Leonard Cheshire to the recipient’s sister, Dorothy Mundon, dated 20 June 1983, in which he tries to reassure her over the circumstances of her brother’s death. £4000-5000

Stephen Burns, a native of Dudley, Worcestershire, enlisted in the Royal Air Force in January 1941 and qualified as an Air Gunner in October 1942.

Posted to No. 57 Squadron, a Lancaster unit operating out of R.A.F. Scampton, at the end of the following month, he served as a Mid-Upper Gunner in assorted crews before joining Sergeant Geoffrey Rice’s aircraft as Rear Gunner. His first sortie - a ‘gardening’ trip flown in early December 1942 - was followed by another eleven operations. Thus regular bombing strikes on such targets as Nuremburg and Stuttgart, in addition to - as per Burns’s flying log book entries - eventful sorties to Essen on 9 January - ‘7 hits by flak’ - and Bremen on 20 February - ‘4 hits by flak’.

On transferring to 617 Squadron April 1943, the recently commissioned Geoffrey Rice and his crew - Burns now firmly embedded as his Rear Gunner - commenced a flurry of low-level cross-country exercises in readiness for Operation “Chastise” on 16-17 May: detailed to attack the Sorpe Dam in 617‘s second wave of five Lancasters, it was Burns’s 13th sortie.

Operation “Chastise”

Owing to the distance and route involved, 617’s second wave was in fact the first to depart Scampton, the five pilots and their crews taking-off in quick succession around 9.30 p.m. First off was Flight Lieutenant Barlow, whose Lancaster was shot down by flak; second, Flight Lieutenant Munro, who had to return to base after his aircraft was hit by flak; third, Pilot Officer Byers, whose aircraft was also downed by flak; fourth, Geoffrey Rice, of whom more later; and fifth, Flight Lieutenant McCarthy, the only pilot in the second wave to achieve some degree of success.

Of the fate of Lancaster AJ-H (ED-396), piloted by Rice, with Burns manning the rear turret, John Sweetman’s Operation Chastise takes up the story:

‘The fourth aircraft in the second wave was not shot down, but it suffered a bizarre experience. Like Munro, its pilot was forced to abort the operation. At 2131 Pilot Officer Rice left Scampton in AJ-H (ED 936/G), also bound for the Sorpe Dam. Navigation presented a problem as, flying entirely alone, the crew found it easy to get off track. Rice admitted that “at times you didn't really know where you were.” Conditions were perfect, however, and the Lancaster crossed the North Sea without trouble. MacFarlane, the navigator, took drifts at intervals by dropping flame floats which the Rear Gunner [Burns] looked at through his reflector sight, confirming that drift was virtually nil. When two minutes short of Vlieland the crew recorded seeing the loss of an aircraft, probably Byers’. At low altitude, once the enemy coast had been identified Rice found the aircraft committed to its crossing point, and at 2259 AJ-H flew over the predicted narrow neck of Vlieland without having made the designated course adjustment at 53°20’N 04°54'E but with the mine fuzed at 2255. Rice was flying so low that he had to pull up over the sand dune, and once across the island he climbed to confirm his position, sank low again and turned south-east along the briefed track. By now Gee had failed and the navigator used another flame float to check drift. As AJ-H flew into the moon, height was difficult to judge, and just short of the Afsluitdijk the flight engineer noticed the altimeter registering zero. He was about to warn Rice, who later blamed himself for not using the spotlights to determine altitude, when a tremendous shudder shook the aircraft. Instinctively Rice pulled it up, and a second “violent jolt” occurred almost immediately. The impact buckled panels of the main section of the fuselage and water hit the roof of the cabin and sprayed over the navigator's charts, to a plaintive “Christ! It's wet at the back” from the rear turret and a terse “You've lost the mine.”

For when AJ-H struck the water, the mine had been torn off. Hitting the fixed tail wheel (the second impact), the mine drove it up through the main spar of the tail plane, shattering the Elsan toilet just forward of the rear turret. Meanwhile, as Rice put the aircraft into a sharp climb, water poured through the doorless bomb bay and down the fuselage. The rear gunner, Burns, up to his waist in disinfectant and salt water, might therefore be excused his mild expletive. AJ-H had cleared the polder (Afsluitdijk) and flew on into the Ijsselmeer before the full extent of its problem became apparent. Loss of the mine was verified as water drained out of the bomb bay once more and a damp rear gunner made himself marginally less uncomfortable.

With the mine gone, for this crew Operation “Chastise” had come to an abrupt halt. Turning back to the north-west at 2306, Rice flew over the polder once more and made an unorthodox exit between Texel and Vlieland ten minutes later. Alert defenders played searchlights across the gap and put up some flak, but AJ-H flew under this and set course for home. Approaching base, Rice sent the flight engineer to check the hydraulic system, and he reported that most of the fluid had been lost. The pilot therefore decided to use the emergency drill, under which an air bottle was used to lower the undercarriage. He feared however, from previous experience, that once the undercarriage had been locked down by this method, insufficient pressure would remain to operate the flaps fully. So the wireless operator warned ground control “aircraft damaged-possibly no flaps” and requested maximum landing room. Rice circled at 1,000 ft. for 20 minutes while the emergency procedure was carried out. Then he ordered all but the flight engineer into their crash positions, with their backs to the main spar and facing aft, as he prepared to set AJ-H down on the long runway. As he did so another Lancaster flew in below him to land: without means of communication, Munro could not call up the tower and had simply gone straight in.

Eventually at 0047 Rice “did a wheeler,” landing with the front wheels down and tail up. AJ-H crunched down on to its tail fins before turning off the runway. Rice switched off, scrambled out of the Lancaster and walked away “very depressed.” Whitworth, who had driven out in his truck, found him, told him to shake out of his mood and gave him a lift to debriefing. Although embarrassed at having made “a complete balls of things,” Rice stayed after debriefing to wait for the other crews. He noted when Gibson came in that the squadron commander’s hair was plastered down with sweat, even though he had flown in shirtsleeves. And later, when he arrived from Grantham, learning the details of Rice's misfortunes, Harris commented: “You're a very lucky young man.” There was, too, an interesting postscript which yet again illustrated the importance of accurate communication. Eaton’s “aircraft damaged - possibly no flaps” had caused consternation in the control tower. “What did you mean ‘without a clutch’?,” a puzzled W.A.A.F. operator asked Rice.

The fate of the lost mine remained uncertain. To the crew’s knowledge it did not explode. Most probably the hydrostatic fuzes failed to work because the water was not deep enough to activate them, the area in which the mine dropped being exposed mud flats or water to the depth of only a few feet. Although some channels could have contained water over 30 ft. deep, a British official source later concluded: “The chances are weighted fairly heavily in favour of it landing in shallow water.” But, armed at 2255, the self-destructive device ought to have worked, and it must therefore be concluded that the mechanism suffered damage during the mine’s unorthodox departure from the aircraft.’

According to his sister, Dorothy - and in common with his fellow ‘Dambusters’ - Burns was the recipient of flurry of local press attention; one journalist called at his parents home without notice, thereby curtailing the gallant Rear Gunner’s waltzing around their sitting-room in celebration of his immediate leave - and survival.

Beyond the Dams

Notwithstanding their adventures in mid-May, Rice and his crew were back in action in July, as operational plans for 617’s future took shape. Thus a long haul to attack the electric power station at Aquata Scriva in Italy on the 15th, with a stop over in Blida, Algeria; a strike on harbour at Leghorn on the return trip to Scampton on the 24th and a run to Turin on the 29th, with another stop over in Blida, in addition to Ras-el-Ma in French Morocco.

Next up, on 11 November, following a move to R.A.F. Coningsby and the appointment of Leonard Cheshire as C.O., was one of 617’s hardest targets, the Antheor Viaduct, from whence the attacking force once again made for Blida; Rice was awarded the D.F.C.

Tragically, however, this proved to be Burns’s penultimate sortie, for he was killed in action in a strike in the armaments factory at Liege in Belgium on the night of 20-21 December 1943. Nearing the target, his Lancaster was attacked by a night fighter and set on fire and, minutes later, plunged into the ground near Merbes-le-Chateau: one local source states that Burns remained at his gun to the bitter end, still firing as the crippled Lancaster took its death plunge.

The fallen airmen’s bodies were recovered by the Germans and buried in Gosselies Cemetery, Belgium. That is except Geoffrey Rice, for he was thrown clear of the burning aircraft and survived. Alan Cooper’s Beyond the Dams to the Tirpitz takes up the story:

‘Rice remembered nothing after giving the order to bale out. At approximately 8.30 the following morning he regained consciousness and found himself in a wood with his parachute hanging from a tree. The wreckage of his aircraft was scattered around, his wrist broken and he had a severe cut over his left eye. Staggering from the wood, he met three farm labourers and after he had told them that he was British, they took him to a farm. Sometime later he was taken to a doctor who set his wrist in plaster.

Over the next few weeks he was moved from town to town in ‘safe’ houses organised by the Belgian Resistance until he ended up in Brussels at the end of January 1944. In April he went by train to Antwerp, but finally, on the 28th, he was reported to the Secret Police and captured. He remained a prisoner until his release one year later. He had been on the run for over four months. The rest of his crew were killed in the crash, although the Red Cross later reported that Sergeant Chester Gowrie, R.C.A..F, the wireless operator had been shot by the Germans.’

Stephen Burns - who died a week short of his 23rd birthday - had, according to Leonard Cheshire, ‘a very distinguished and gallant operational record’:

‘His work has at all times been of the very highest order and, as Rear Gunner, has been of the greatest importance. He shouldered his responsibility with great confidence and proved that he was equal to any task he might be given. I can assure you that his loss has been received by everyone with the greatest sorrow and I would like to send you on behalf of the whole Squadron my most heartfelt sympathy in the anxious days awaiting which now lie ahead ... ’

Confirmation of Burns’s death was received by his mother from the International Red Cross on 16 February 1944.

Share This Page