Lot Archive

Sold by Order of the Family

‘He was a young, inexperienced officer, comparatively recently commissioned from the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. Yet he set an example of the highest gallantry that may be asked of any Briton: he sacrificed his life rather than dishonour his nation. Surely his death, chosen so selflessly and so courageously at Pyongyang, must stand with the finest epics of personal courage in the history of British prowess.’

Final paragraph from Waters’ original G.C. recommendation, later omitted from the London Gazette citation.

‘Among Gloucesters who fought in this battle, it was universally agreed that ‘A’ Company had the roughest handling of all: the company commander, Major Pat Angier, had been killed, as had VC winner Lieutenant Phil Curtis and Second Lieutenant John Maycock; Lieutenant Terry Waters, severely wounded in the head, was only prevented from going back to his platoon by the physical interventions of Captain Bob Hickley the Medical Officer.’

Korea: The Commonwealth at War, by Tim Carew

The important and highly emotive Korean War posthumous G.C., ‘Battle of Imjin River’ M.I.D. group of three awarded to Lieutenant T. E. Waters, West Yorkshire Regiment, attached 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, who, after being recognised for gallantry at the Battle of the Imjin River, was captured and imprisoned in the foul conditions of the Kangdong Caves where he died having refused to accept medical treatment, better food, and other amenities in exchange for his participation in propaganda on behalf of the North Korean Communists.

At the Imjin, 22-25 April 1951, Waters’ A Company withstood the brunt of repeated frenzied attacks by a large force of Chinese troops, suffering severe casualties including the deaths of all its officers with the exception of Waters who, although wounded in the leg, skilfully assumed command of the Company at this critical period. Badly wounded in the head later in the battle, he was recommended for a Military Cross for his ‘splendid example of coolness and gallantry’ by 1 Glosters Commanding Officer J. R. ‘Fred’ Carne V.C. D.S.O.; the award was later revised to an M.I.D. solely on account of his death in captivity - posthumous M.C.s were not permitted.

Captured subsequent to the Battle, Waters endured a march of immense hardship followed by imprisonment in the dark and partially flooded tunnels near Pyongyang known as the ‘Caves’ where numbers died daily from wounds, sickness, and malnutrition. Eventually, as the only officer with the British party, he ordered his men to save themselves by pretending to accede to subversion at a Peace Camp while, although in rags, starving, and badly wounded, steadfastly refusing to do so himself. He died a short time later.

‘Irrespective of his service and youth, he was an officer representing the British Commonwealth in enemy country: by his actions, the Commonwealth’s reputation would be judged. Quite simply, he was given a choice: life, and agreement to reject, at least outwardly, the principles for which he was fighting in Korea; or a steadfast adherence to those principles - and death. Coolly, loyally, like the gallant officer he was, he chose death.’

George Cross, reverse of cross engraved ‘Lieut. Terence E. Waters. W. Yorks.’; Korea 1950-53, 1st issue, with M.I.D. oak leaf (2/Lt. T. E. Waters. W. Yorks.); U.N. Korea 1950-54, unnamed as issued, extremely fine (3) £140,000-£180,000

G.C. London Gazette 13 April 1954 Lieutenant Terence Edward Waters (463718) (deceased), The West Yorkshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Own), attached The Gloucestershire Regiment.

‘Lieutenant Waters was captured subsequent to the Battle of the Imjin River, 22–25 April 1951. By this time he had sustained a serious wound in the top of the head and yet another most painful wound in the arm as a result of this action.

On the journey to Pyongyang with other captives, he set a magnificent example of courage and fortitude in remaining with wounded other ranks on the march, whom he felt it his duty to care for to the best of his ability.

Subsequently, after a journey of immense hardship and privation, the party arrived at an area west of Pyongyang adjacent to P.W. Camp 12 and known generally as “The Caves” in which they were held captive. They found themselves imprisoned in a tunnel driven into the side of a hill through which a stream of water flowed continuously, flooding a great deal of the floor in which were packed a great number of South Korean and European prisoners-of-war in rags, filthy, crawling with lice. In this cavern a number died daily from wounds, sickness or merely malnutrition: they fed on two small meals of boiled maize daily. Of medical attention there was none.

Lieutenant Waters appreciated that few, if any, of his numbers would survive these conditions, in view of their weakness and the absolute lack of attention for their wounds. After a visit from a North Korean Political Officer, who attempted to persuade them to volunteer to join a prisoner-of-war group known as “Peace Fighters” (that is, active participants in the propaganda movement against their own side) with a promise of better food, of medical treatment and other amenities as a reward for such activity—an offer that was refused unanimously—he decided to order his men to pretend to accede to the offer in an effort to save their lives. This he did, giving the necessary instructions to the senior other rank with the party, Sergeant Hoper, that the men would go upon his order without fail.

Whilst realising that this act would save the lives of his party, he refused to go himself, aware that the task of maintaining British prestige was vested in him.

Realising that they had failed to subvert an officer with the British party, the North Koreans now made a series of concerted efforts to persuade Lieutenant Waters to save himself by joining the camp. This he steadfastly refused to do. He died a short time after.

He was a young, inexperienced officer, comparatively recently commissioned from the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, yet he set an example of the highest gallantry.’

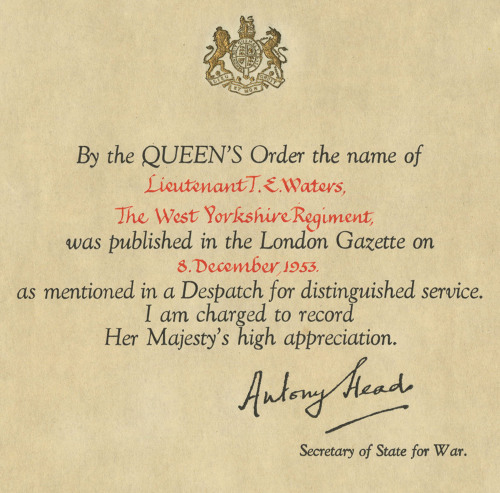

M.I.D. London Gazette 8 December 1953.

The original recommendation (for a Military Cross), initiated by Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. ‘Fred’ Carne V.C. D.S.O. (who Commanded the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment during period covered by citation) states:

‘Lieutenant Waters was a platoon commander of A Company, 1 Glosters. During the opening phase of the Battle of the Imjin River on the night of the 22/23 April 1951, A Company were heavily attacked by a large enemy force. Withstanding repeated attacks for about eight hours, the Company suffered severe casualties and all officers, with exception of Lieutenant Waters were killed. Assuming command of the Company at a most critical period, about 0650 hours on 23 April, Lieutenant Waters quickly grasped the situation and reorganised the Company. Then, when ordered to withdraw, he extricated the Company with great skill from a dangerous situation, and brought it back to the Battalion HQ area.

During the final phase of the battle on the night of 24/25 April 1951, Lieutenant Waters was again commanding his platoon. Once again A Company received the brunt of the enemy attack which was carried out with great ferocity. Lieutenant Waters set a splendid example of coolness and gallantry; eventually he was severely wounded, but he refused to leave his men until he was ordered to do so. Throughout this battle, Lieutenant Waters devotion to duty, his personal gallantry, and his able leadership were of the highest order.’

Terence Edward Waters was born in Salisbury, Wiltshire on 1 June 1929, the son of Albert Edward and Muriel Olive Waters (née Apperley). After leaving Bristol Grammar School, where he held the rank of Sergeant in the School’s Cadet Force, Waters was accepted into the Royal Military College Sandhurst in 1948 and the following year commissioned Second Lieutenant into the West Yorkshire Regiment, then part of the British Occupation Forces in Austria. Volunteering for Korea he went out with the Northumberland Fusiliers in December 1950 before being seconded to the 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment which formed part of the 29th Independent Infantry Brigade. Posted to A Company under Major P. Angier, Waters was present a the Battle of the Injim River, 22-25 April 1951, where his Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. Carne) was subjected to an almost continuous assault by vastly superior force of Chinese troops over a period of three days.

A Company, 1st Gloucesters at the Battle of the Imjin River

On 22 April 1951, the four widely dispersed battalions of Brigadier Brodie’s 29th Brigade, occupying a vital sector of the U.N. line near the Imjin River, were readying themselves for battle. On their left was the 1st Gloucesters, whose A Company (Major P. Angier) was the left forward Company on a hill feature known as Castle Hill, covering the main crossing point of the river 2000 yards to the north:

‘Forward on Castle Hill, commanding the long spurs that rose almost from the southern bank of the river, holding in part the hard dirt road that ran through the cutting along their right flank, was A Company, Pat’s boys, so like the rest in that they were a mixture of both seasoned and green men; in that they knew themselves to be, assuredly, the best men in the whole Battalion. Yet different, in that they were stamped by Pat’s own character, and marked by their own past record in battle and at rest.’ (The Edge of the Sword by Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockely D.S.O., M.C. refers)

Earlier in the day, patrols had reported the presence of the enemy in considerable strength and customary probing attacks were fully expected. By 2230 hours however, large numbers of the Chinese 187 Division were seen wading across the Imjin. Artillery and mortar fire inflicted significant casualties among the massing body of Chinese infantry as they closed up on the North bank of the river, whilst a forward patrol under Lieutenant Temple raked fire on those wading across, holding their position until their ammunition was exhausted. It was the start of a major assault. While Temple’s platoon was delaying the Chinese, two other Battalions of the 187 Division had crossed the river some one and a half miles further to the west and directed their attack on to A Company.

Appreciating that valuable time had been lost in crossing the river, the Commander of the Chinese 187 Division was determined to overrun the Glosters and his first objective was Castle Hill where 2 Platoon (Lt. Waters) held the ridge to the west whilst 3 Platoon (Lt. Maycock) held the summit and further to the rear was 1 Platoon (Lt. Curtis). During the night, A Company, outnumbered by six to one, withstood wave after wave of attack but, having infiltrating themselves between A Company’s forward platoons in the early hours of the 23 April, the Chinese then managed to establish themselves in strength on the top of the hill and had positioned a machine gun in a bunker. In the half light of dawn hundreds of Chinese troops could now be seen milling around the Company position. It was during this phase of the Battle that Waters was wounded in the leg and Lieut. Curtis killed winning a V.C. in carrying out Major Angier’s orders to restore the forward positions on the summit. An evocative photograph, taken the previous morning, records how the Glosters’ Chaplain had visited these two young subalterns at A Company’s position and given them Holy Communion in advance of St. George’s Day. By some haunting coincidence they would both shortly afterwards receive the highest awards for bravery and the communion would prove to be their viaticum - the Eucharist given to a dying man.

As dawn broke on the 23 April ‘A’ Company appeared all but a spent force without any prospect of reinforcements - Lieutenants John Maycock and Philip Curtis were dead and Waters had been badly wounded:

‘When Major Pat Angier telephoned Battalion Headquarters for orders, Tony Farrar-Hockley has recorded that, for the first time since the battle began, he detected a faint tremor in Fred Carne’s hand as he poised a hand over the inevitable pipe. For Carne had to give an order which virtually condemned some thirty men to wounds, mutilation and death.

Not that Angier complained about this order; indeed he was not greatly surprised by it. He was merely a company commander and a professional soldier reporting a a situation of extreme gravity as he saw it himself. On the wireless to Farrar-Hockley, Angier said calmly and regretfully: “I’m afraid we’ve lost Castle Site. I want to know whether I’m to stay here indefinitely or not. If I am to stay, I must be reinforced as my numbers are getting very low.”

Farrar-Hockley called the C.O. to the set, and Carne gave an order, and it was this order which explained the sudden clenching of his teeth on his pipe and the tremor in his hand as he re-lit it: “You will stay there at all costs until further notice - at all costs.”

Anthony Farrar-Hockley marvelled at this Commanding Officer of his, who was seeing his battalion, the battalion he had served for a quarter of a century, shot to pieces all around him. Pat Angier’s last words were: “Don’t worry about us; we’ll be all right.”

He was killed a quarter of an hour later.’ (Korea - The Commonwealth at War by Tim Carew refers)

By 08.30 hours it had become apparent that A Company’s position had become completely untenable. Although the Chinese were paying a huge price for their gains, little by little ‘A’ Company were being swamped by a tide of men and the order to withdraw was given. The company’s 53 remaining men pulled back to Gloster Hill under their one surviving but wounded officer, Waters.

The battle continued in attritional fashion until dusk on 24 April when, with his units becoming encircled, Colonel Carne realised that his battalion could only survive the night in a tight perimeter and, accordingly, moved all his men to the slopes around the top of Hill 238 (now termed Gloster Hill). ‘A’ Company, now under Captain ‘Jumbo’ Wilson, with Donald Allman, the Assistant Adjutant assuming the role of a Platoon Commander and Terry Waters back in charge of his platoon, were ordered to hold the north west end of Gloster Hill including its very highest part - point 235, which the Chinese then attacked with concentrated force, further decimating the Company and rendering Waters unconscious with a dangerous head wound:

‘It is morning. Beyond Hill 235, a sudden rush has driven back Donald’s little group. They withdraw under heavy mortar fire which intensifies as they reach the top of Point 235. The air is black with mortar smoke; it seems as if a huge, dark screen has been dropped across the top of the hill. Men come staggering back from Terry’s position; eleven men, wounded, come reeling back, their senses bemused by shock and injury. The face of one man has been laid open by a splinter of metal; another’s arm is hanging limply by his side, the bone smashed. Sergeant Pugh has been wounded in the shoulder, but he has refused to go back and is helping to reorganise the position. Two men are carrying Terry back; he is quite unconscious from a wound in the top of his head. They lay him down in a slit trench and one of the medical orderlies begins to bandage his head.’ (The Edge of the Sword by Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley D.S.O., M.C. refers)

Tony Farrar-Hockley, the Glosters Adjutant and fighting infantryman to the core would rally the remnants of A Company, some thirty men in all, and briefly retake the hill amid desperate fighting, adding a D.S.O. to his Second World War accolades, but it was becoming painfully apparent that the sands had all but run out. The 700 man battalion’s resistance against an estimated 11000 Chinese Communists was finally being overcome. ‘A’ Company were down to three rounds per rifle, a magazine and half for the Brens and half a magazine for the Stens. At 10.00 on 25 April Colonel Carne summoned his Company Commanders and ordered them to break out independently and to attempt to reach the U.N. rearguard some six miles to the south. With the exception of 46 men, mostly D Company, all were captured including Waters who began a 200 mile forced march of immense hardship and privation.

Waters’ gallantry during the battle resulted in him being recommended for the Military Cross, which, following his death was posthumously revised to a Mention in Despatches - see footnote.

Forced March - The ‘Caves’ - George Cross

In clusters and columns, the prisoners were shepherded off the battlefield toward the remote north. For the captured men, three days of fighting would typically be followed by two and half years of captivity. Waters was held for a time with thirteen other wounded prisoners of war at a Chinese Casualty Clearing Post near Kaesong, South Korea although medical treatment was minimal or non-existent. He had an open scalp wound. He was also wounded in the leg and according to some reports in the upper arm also. During the next three weeks, his party was marched northwards through various prisons and wayside hospitals, sometimes under Chinese guards, at other times with North Korean Escorts. The entire party was weak through lack of food and the urgent need of medical attention. Another Gloster prisoner in the group, Sergeant P. J. Hoper, testified later as to Waters self-sacrificing leadership on the journey: ‘Throughout this period Lieutenant Waters set a wonderful example, by his selflessness and endurance of great pain without complaint. I twice advised Lieutenant Waters to fall out but he refused. Eventually on the last day of the march he collapsed. He rejoined the group some five hours later in Pyongyang, North Korea. Two days later we moved to an area known as ‘The Caves’ (recorded now as PW Camp No 12).

The inhumane treatment of British and American prisoners of war by their Communist captors during the Korean War has been well documented but the events which unfolded concerning Waters at the Caves are surely unique. Farrar-Hockley, himself a British Officer held captive by the North Koreans, understood better than most the dilemma that Waters faced but, writing some years later, he still expresses awe at Waters’ principled and courageous stance:

‘Of all the many stories of gallantry and selflessness on the part of prisoners in these caves, I will recount only one here: a story that was told us later by men who had formed part of it; a story which provided us with inspiration to continue resistance to our captors during the most difficult moments. Terry - the last remaining platoon commander of ‘A' Company - was taken to “The Caves” in the summer of 1951. He had been a member of a column of seriously wounded captives which had marched slowly north from, the Imjin River some little time after the two main columns had set off. Though he was in great pain from a wound in his leg and a terrible head injury, Terry set a splendid example on the march, caring, as best he could, for other serious casualties with him. By the time they reached “The Caves”, the condition of many prisoners had deteriorated dangerously; for they had had no medical attention of any sort en route and many still wore the dressings, by now ragged and filthy, placed on their wounds by our own medical staffs before capture. Terry, and Sergeant Hoper of the Machine-gun Platoon, were placed with a number of others from the column in a cave already crowded with Koreans themselves dying of starvation and disease. Except when their two daily meals of boiled maize were handed through the opening, they sat in almost total darkness. A subterranean stream ran through the cave to add to their discomfort, and, in these conditions, it was often difficult to distinguish the dead from the dying.

One day, a North Korean colonel visited them to put forward a proposition.

“We realise,” he said, “that your conditions here are uncomfortable. We sympathise. I, myself, am powerless to help you - unless you are prepared to help us. If you care to join the Peace Movement to fight American aggression in Korea, we can take you to a proper camp where, in addition to better rations and improved accommodation, your wounds will be cared for by a surgeon.”

Our men refused this offer, individually. But Terry, seeing their condition, their numbers dwindling, came to a decision on which he acted the next morning. He drew Sergeant Hoper to one side and said:

“I have thought this business over and have decided that you must go over to the ‘Peace-Fighters’ Camp. Most of you will die if you stay here. Go over, do as little as you can; and remember always that you are British soldiers.”

“What about you, sir?” asked Hoper.

“It is different for me,” said Terry. “I am an officer; I cannot go. But I order you to go and to take our men with you.”

Terry remained firm in his decision; and when the North Korean colonel returned, as they had guessed he would, Sergeant Hoper and his party left “The Caves” with a group of American soldiers.

The colonel pressed Terry to accompany them, advising him that he would not accept a final refusal just then but would return later.

He returned four times. Armed with promises of an operation on Terry’s wounds by a surgeon, and of a special diet of eggs, milk and meat in place of the boiled maize, he failed each time.

Terry was a young subaltern, not long out of the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. Yet, irrespective of his service and youth, he was, he saw clearly, an officer representing the British Commonwealth in enemy country: by his actions, the Commonwealth’s reputation would be judged. Quite simply, he was given a choice: life, and agreement to reject, at least outwardly, the principles for which he was fighting in Korea; or a steadfast adherence to those principles - and death. Coolly, loyally, like the gallant officer he was, Terry chose death. And so he died.’ (The Edge of the Sword by Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockely D.S.O., M.C. refers)

Waters was posthumously awarded the George Cross, the medal being presented to his parents at Buckingham Palace on 6 July 1954. He has no known grave and is commemorated at the U.N. Memorial Cemetery at Busan, South Korea and on war memorials in Stoke Bishop and at Westbury-on-Trym, near Bristol.

Footnote:

A quantity of correspondence held at the National Archives reveals the extent and nature of the deliberations which took place at the War Office prior to the announcement of the gallantry awards in respect of the Korea Campaign. These discussions were particularly protracted due to the lack of immediately available witnesses to the events at the Battle of the Imjin River - most of the surviving officers remained incarcerated until the middle of 1953. One particular letter, written in November 1953 by Lieutenant-General Sir Euan Miller, K.B.E., C.B., D.S.O., M.C., Military Secretary of the British Army to Lieutenant-Colonel J. P. Carne, O.C. 1st Glosters, centres on the Honours and Awards Committee’s ruling regarding posthumous awards and confirms that Waters’ M.C. was downgraded to a ‘Mention’ only on account of the fact that his death as a P.O.W. occurred before his M.C. recommendation could be submitted:

‘My dear Carne,

Thank you for you letter of the 2nd November about your list. Of course I agree that the action of your Battalion deserves full recognition and your remarks on the action will be seen by the Military Members of the Army Council when I discuss it with them.

Meanwhile we are progressing a bit. At ‘A’ attached is the order of merit that my office received from Farrar-Hockley in your name. I take it that this was correct. Since then we have been into this with the Honours and Awards Committee and I am afraid that they have ruled quite definitely that the recommendations have to be made while the individuals are known to be alive. Therefore no awards to those who died as prisoners of war are allowable, except the Victoria Cross, the George Cross, and Mentions-in-Despatches. This eliminates from the MC list Washbrooks and Waters, and from the MM list Hurst and Gallop. I understand, however, that Waters may be recommended for a George Cross for his work as a prisoner. My staff went into this again with Farrar-Hockley and produced a revised order of priority as shown in attached ‘B’.

I should be glad if you let me know that you agree with this order of priority.’

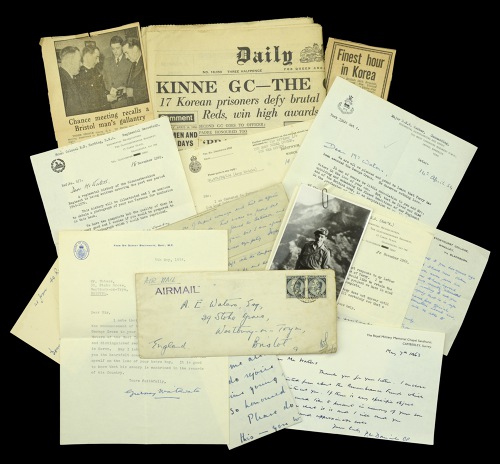

To be sold with the following archive:

(i) A letter to Mrs A. E. Waters from Lieutenant-Colonel Digby Grist, 1 Glos. Regt., dated at the South Bank of River Han, 4 May 1951, in which he regrets that Terry Waters is missing as a P.O.W. and describes the gallant and effective part played in the Battle of the Imjin River by Waters and A Company:

‘...His Company, A, bore the brunt of the first Chinese attack on the night 22/23rd. They held it splendidly and at dawn it appeared that the enemy were withdrawing, but they were reinforced by huge numbers, and attacked again - this time simply swamping the defence by weight of numbers. It was then that Pat Angier, the Company Commander, and Maycock and Curtis, the two Platoon Commanders were killed. From then on only Anthony Wilson and Terry were left with the Company, but there was still two days fighting to do, and they like everyone else did splendidly.

There is no doubt in anyone’s mind out here that the action of the Battalion was one of superb courage and that its effects have already been very considerable. That makes us proud but it doesn’t lessen the sadness... with my sincerest sympathy, Digby Grant’

(ii) A letter to Mr A. E. Waters from Rev. W. R. Thomas, Stoneyhurst College, dated 27 September 1953, expressing hope for Terry’s safe return and regret at not having seen his name among those of released P.O.W.s.

(iii) A letter to Mr A. E. Waters from Major D. R. W. Webber, Commanding West Yorkshire Regimental HQ and Depot, dated 14 April 1954, offering condolences to him and his wife on the loss of their son but expressing pride that ‘he lived and died upholding and enhancing the finest traditions of our Regiment and of the British Army’.

(iv) A letter to Mr Waters from G. D. Gregory, dated 17 April 1954 expressing pleasure at having read of Terry’s G.C. award and conveying further information and sentiments:

‘Curiously enough I met quite by chance last November the Second-in-Command of his company, an old Downside boy, who told me for the first time the story of Terry’s last days... Needless to say the school cadet force, which was always proud to count Terry among its members, will be enormously inspired by this splendid award.’

(v) A letter to Mr Waters from Viscount W. J. Slim, Colonel of the West Yorkshire Regiment and Governor-General of Australia, dated at Government House, Canberra on 26 April 1954 offering the ‘deep sympathy of all ranks of the West Yorkshire Regiment at the loss of your son...’ and concluding ‘it is not how long a man lives but what he does with his years and your son did much with his that will be remembered.’

(vi) A letter to Mr Waters from Sir Gurney Braithwaite, Bt., M.P., dated 5 May 1954: ‘offering you the heartfelt condolence of Lady Braithwaite and myself and on the loss of your brave boy. It is good to know that his memory is enshrined in the records of his country.’

(vii) A Central Chancery letter to Mr A. E. Waters regarding an Investiture at Buckingham Palace on Tuesday 6 July 1954.

(viii) Investiture at Buckingham Palace programme dated Tuesday, 6 July 1954.

(ix) The recipient’s M.I.D. certificate, together with forwarding letter from the Army Medal office for the Certificate and the recipient’s Oak Leaf Emblem.

(x) A photograph of the recipient and Lieutenant P. Curtis of A Company taken by the Regimental Chaplain shortly before the Battle of the Imjin, handwritten by latter on the reverse:

‘Lt. Philip Curtis, V.C. & Lt. Terence Waters, G.C. in the ruined temple in “A” Coys’ lines (photo taken by Padre Davies, a few minutes after Holy Communion). The day is Sunday, April 22nd, the time is 1 o’clock. The Battle of the Imjin is about to begin. S. J. Davies, Chaplain.’

(xi) A further quantity of photographs including a studio portrait of the recipient in uniform; an image of the recipient in uniform taken outdoors in a mountainous terrain and a group photograph of officers of the Gloucestershire Regiment.

(xii) A further quantity of correspondence, programmes and ephemera including letters of condolence and invitations to memorial dedications and commemoration services.

(xiii) The Imjin Roll by Colonel E. D. Harding; Bristol Grammar School Chronicle Vol XXVI No.12, July 1954; The Back Badge - The Journal of the Gloucestershire Regiment, Summer 1954 and CA IRA XIV - The Journal of the West Yorkshire Regiment Vol XV.No. 6. these last three each containing a tribute to the recipient.

(xiv) A copy of the London Gazette of 13 April 1954, containing the recipient’s George Cross citation; and a quantity of other newspaper cuttings.

Share This Page